Master of Wine Cathy van Zyl reviews the vinous state of the Japanese nation.

“Wine”. It’s not a word you would readily associate with Japan – Mount Fuji, cherry blossoms, samurai, sushi, rice, sake and bullet trains would probably top the list. |

But, increasingly, the country’s very (very!) small wine industry is attracting the attention of critics, the UK’s Jamie Goode and this author included, who would like to see more Japanese wines – made from Japanese grape varieties – gracing the tables of the islands’ restaurants.

This industry deserves definition – by way of semantics and numbers.

By semantics: The National Tax Administration Agency (NTA) defined “Japanese wine” as recently as October 30, 2015 as being wines produced in Japan using grapes cultivated in Japan. Prior to that date, “Japanese wine” also included wines processed in Japan from bulk wines imported into the country and wines made in Japan from reconstituted grape must. These two categories are now defined as “domestic wine”.

By numbers: The production of Japanese wine in 2019 topped just 16 612 000ℓ - and accounted for just 4.6% of all wines distributed in the country. To put this in perspective and provide some context, in 2018 South Africa produced 960 000 000ℓ.

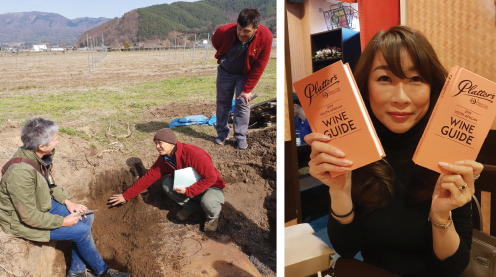

ABOVE: Cathy van Zyl and renowned local viticulturist Rosa Kruger snapped at a dinner at Chateau Mercian.

Imports account for 66% of the market (42% bottled wine, 9.6% sparkling wine and 15% bulk wine) and domestic wine 28.9%. In other words, Japanese wine makes up less than 15% of the total produced in Japan.

The reasons for the industry’s small size are two-fold.

Firstly, while Japan’s land mass at 37 800 000 hectares is almost the same as Germany, some 75% of the land is mountainous and practically impossible to cultivate. Simply, land on which to grow grapes is a scarce resource.

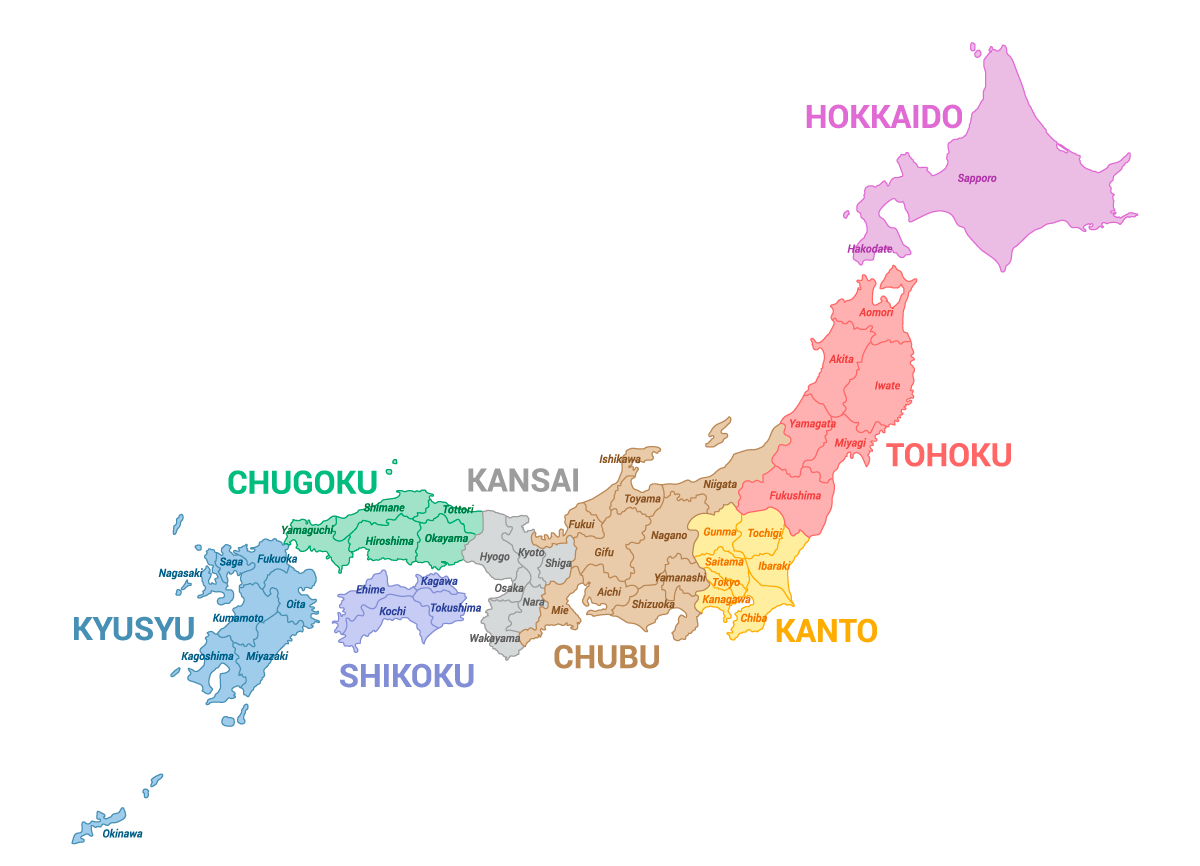

The archipelago stretches north and south, and vines are grown in basins, on mountains and hills, and near the coast. The climate differs vastly from Hokkaido in the north, where upwards of a metre of snow in winter is common, to Kyushu in the south, where the maximum temperature exceeds 30 degrees in the summer.

In general, Japan has a higher rainfall and is more humid compared to the major European production areas, and obviously than South Africa. Also, there is a 23° difference in latitude between Okinawa and Hokkaido, whereas France spans just six degrees.

ABOVE: South African viticulturist Rosa Kruger sharing knowledge with Japanese counterparts at Chateau Mercian. A vine is only as good as its root system … The increased exposure of South African wines to the Japanese market means that the Platter Guide is a useful resource.

Somewhat surprisingly, all 47 prefectures grow grapes. The three main wine regions are Yamanashi (which produces 31.2% or 5 189 000ℓ), Nagano (23.8% or 3 950 000ℓ) and Hokkaido (15.7% or 2 603 000ℓ) with Yamagata (7.0% or 1 159 000ℓ), Iwate (3.5% or 580 000ℓ) and Okayama (2.4% or 394 000ℓ) following. The remaining 41 prefectures together account for 16.5% (2 737 000ℓ).

Secondly, wine is a relatively new industry for Japan officially debuting just over 140 years ago in 1874 during the Meihi era when Kofu Yamanori and Norihisa Takuma followed the step-by-step instructions in books foreign visitors had left behind.

Just a few years later in 1877, Ryuken Tsuchiya and Masanari Takano journeyed to Troyes in France to study viticulture and winemaking.

Other innovators included Kotaro Miyazaki who made wine with Tsuchiya and Takano at Dainippon Yamanashi Wine Company, Japan’s first wine company, after their return from France; Zenbei Kawakami who opened

the Iwahara Hara Vineyard in 1891; Kamiya Denbei who built the Ushiku Chateau in 1903; and Shinsuke Koyama and his Tomi Vineyard in 1904.

The first Japanese Master of Wine, Kenichi Ohashi, is a frequent visitor to South Africa, having been mentored through his years of study by the author.

Despite these efforts, dry table wines were not accepted in the Japanese diet at the time, and most of the production was sweet, fruity beverages from imported grape concentrate and wines, as mentioned. In recent years, there has been a dramatic swing towards making wine from Japanese-grown grapes.

Today, there are 331 wineries in Japan, up by 28 wineries since 2018. Yamanashi leads the charge with 85 wineries, Nagano has 38, Hokkaido 37 wineries, Yamagata 15 and Iwate 11. The largest producer is Hokkaido Wine, which produces 2.6 million bottles a year. The majority are much smaller.

Currently plantings slightly favour white varieties – 45.9% versus 43.3%. In addition to the vinifera varieties of chardonnay, pinot gris, sauvignon blanc, kerner (whites), merlot, cabernet sauvignon, cabernet franc and pinot noir (reds), there are the relatively disease resistant hybrids and labruscas campbell early, Niagara and Delaware.

But if there’s one wine associated with Japan it’s koshu, a pink-skinned big-berried hybrid grape that is used to make white wine. At number one (16.1%) it gets its hybrid status because it is one quarter vitis davidii, which is a wild grape from southern China. It is virtually synonymous with the Yamanashi prefecture, where each year each and every bunch is topped by a little white “hat” to protect it from the abundant summer rains in the lead up to the harvest. At number two is the big berried muscat bailey A (14.2%), a 1927 cross by Zenbei Kawakami from bailey and muscat hamburg.

ABOVE: Japan’s islands vary vastly in temperature and growing conditions from north to south.

Others (from position three to seven) are niagara, concord, delaware, merlot and chardonnay. But you’ll also recognise pinot noir, zweigelt, kerner, muller-turgauri, sling and semillon. Kellner (white) and pinot noir (red) are the most planted varieties in Hokkaido; sauvignon blanc and merlot in Nagano.

Also making waves is albarino made in the Niigata and Toyama prefectures (cool areas of the Sea of Japan), syrah grown by Mercian Mariko Vineyard and others in Nagano and petit verdot of Rubaiyat Winery (Katsunuma in Yamanashi).

The best description for most Japanese wines is “delicate” and “pure” – the grapes just don’t achieve the levels of ripeness they would need to be described as “ripe and fruity”. As such, they match much of the Japanese cuisine, especially sushi.

Importantly, for the future of this small industry, Japanese palates are changing, and people are starting to alter their alcohol choices, from sake and beer to wine. This has been encouraged by greater visibility of Japanese wines in retail stores and restaurants, and by the popularity of food and wine pairing. Restaurants, too, previously only offered bottles, but now they serve by the glass, which means patrons can try more than one wine.