Love it

or leave it?

There’s a new grape in town … Just like chenin blanc it’s been used and abused for making brandy or large volume big blends. Has the time come for colombar to be recognised?

Twenty years ago, when sauvignon blanc was only just beginning to gain traction among white wine drinkers the terms used to describe it were somewhat odd. After all, who wanted to put a glass to the lips when commentators and critics were saying that it smelled like “cat’s pee on a gooseberry bush” or “sweaty armpit”?!

Appropriate and accurate since many of those early sauvignon blancs were scarily reminiscent of a Tom Cat having scent-marked his turf – but it was odd nonetheless. And the sweaty armpit? Well, scientific boffins narrowed that chemical compound down to mercaptans – of which 3-mercaptohexyl acetate (or 3MHA for short) – was the culprit. It’s also known for being the aromatic compound associated with passion fruit or granadilla aromas.

Winemakers worldwide realised that consumers weren’t wild about it and have got to grips with this aromatic compound and it’s no longer a feature of sauvignon blanc tasting notes. The other grape frequently associated with sweaty armpits is colombar or colombard.

Interestingly enough, it falls between chenin blanc and chardonnay in terms of its share of the South African national vineyard. Chenin makes up 18.6% of all white plantings, colombar 11.42% and chardonnay 7.1% – so why don’t we see more of it on the retail shelf?

There are a number of reasons for this – but first a bit of background. Much like cinsaut/cinsault colombar is also often spelled colombard, and that’s because of its French origins. It’s a grape that has been planted in local soils since the 1920s. Unsurprisingly it was planted here for brandy production because it has good acidity and it crops heavily, delivering 15 to 20 tons per hectare. Compared to the 6 tons per hectare that quality focussed chardonnay and cabernet sauvignon producers insist on, that’s a massive difference to the farmer's pocket and bank balance.

Gnarled bush vines as far as the eye can see. The Swartland is a treasure trove of old vines.

Most plantings can be found in warmer, lower rainfall areas – notably the Breedekloof and Robertson areas as well as in the Northern Cape where producers rely on irrigation. In the green vineyard swathes on the banks of the Orange River some farmers proudly recount how they can take off 30 or even 40 tons of fruit from their vines!

It was around the 1970s that a few of the co-operative wineries began bottling colombar on its own – as an everyday quaffer. Light, pleasant and relatively simple.

As John Platter wrote in his 1995 annual Guide: “Colombard: Has sometimes produced exciting, pleasantly fresh wines, suffused with guava, granadilla and fresh fermentation character plus acidity for crispness, and, specially from the Breede River regions, with attractive fruity flavours. But they (certainly the drier styles) are not made for extended cellaring. They are intended to be quaffing wines consumed when young and fresh. Colombard was imported from France as a grape for brandy making, in which role it still performs too.”

They are intended to be quaffing wines consumed when young and fresh.

In that edition of the Platter Guide, there were two wines which scored 4 stars, both from (then) co-operatives, Nuy and Swartland. Fast forward 27 years and that same annual publication acknowledged its first ever 5 star rating, this time for a miniscule single bottling, the Naudé Langpad 2021. It’s an altogether more serious wine, thrilling and exciting with its minerality and vivid acidity.

“The really interesting thing for me is that people don’t like to know what the grape is. Colombar is almost seen as a second-class citizen or at least uncool. They will always ask for the Langpad or the Smurfie.” It’s known among fans as the Smurf wine because it has a distinctively bright blue wax capsule. And that was not by design, Naudé acknowledges. It just happened to be what was available when the wine was being bottled and labelled! “But customers seem to like it …” he says with a shrug of his shoulders.

The wine is from a single vineyard near Vredendal that was planted in 1985. Platter thought it a “superb expression of apple blossom, Pink Lady, hint of spice. Textured and pristine a salty wet stone nuance to the finish. Unoaked.”

His interest in colombar came from his mentorship of talented younger winemakers, fresh from Elsenburg agricultural college – notably Sakkie Mouton. Mouton, who grew up on the West Coast, made a single barrel of chenin blanc which blew the proverbial socks off visiting Master of Wine and influential critic Greg Sherwood. With its irreverent label reminiscent of a schlock horror movie poster, that first Revenge of the Kreef became the stuff of wine legend and myth, rarer than hen’s teeth.

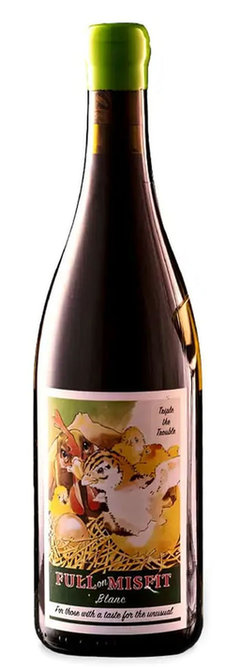

Changing the face of colombar, one wine at a time

Mouton followed it up with a white blend, called the Full On Misfit. The latest bottling is a blend of 55% colombar, 21% chenin blanc, 19% palomino and 5% chenel. (The same colombar, coincidentally, that Naudé used for the Langpad.) Here’s what Sherwood wrote about that wine: “The 2021 Full On Misfit blanc 2021 is an incredibly well assembled wine bearing all the hallmarks that have made Sakkie Mouton’s previous releases so collectable. The aromatics scream West Coast terroir with layers of salinity, sea breeze and dried kelp over more linear expressions of white peach, freshly squeezed guava, pear puree and honeydew melon nuances. The ever-present crushed granite minerality adds extra complexity and character but also ensures that the wine never becomes too overtly fruity but rather errs on the side of a leaner, classical textural restraint. The palate on this young wine shows fabulous crystalline purity and freshness with yet more waves of crunchy peach fruits, maritime salinity and delicate savoury notes of Japanese nori. The finish is taut, pithy and electric with a fine glycerol mid-palate balance and attractive hints of dried orange peel, lime cordial and brine.” Sherwood scored the wine 94 out of a possible 100 points.

The new colombar wines exciting consumers include the Patatsblanc, probably the first to attract attention, made from old vines near Montagu which were rescued by Fritz Schoon, Henk Kotze and Reenen Borman of Boschkloof. The debut vintage was 2015. “Grapefruit to the fore, threaded with the same savoury and complex colouring – beeswax, minerality, peach kernel. Quite individual,” wrote taster Christine Rudman in the 2018 edition of Platter.

Boschkloof vineyards in Stellenbosch might not include colombar but Rheenen Borman's faith in colombar is evidenced in the Patatsfontein wines (Image: Boschkloof FB)

Then there’s Bertie Coetzee of Lowerland with the 2020 Vaalkameel colombard, a 92 pointer in Platter. Coetzee’s organic offering is from Prieska, along the banks of the Orange River in the Northern Cape. Others to look out for include Arendsig from Robertson, The Fledge of Calitzdorp, but made from Swartland fruit, and Micu Naransky’s La Complicité which is idiosyncratically wooded.

For wine cognoscenti, there are echoes of the early days of the chenin blanc revival. So expect to see more labelled colombar(d) appearing on retail shelves in coming years. Who knows, in another 20 years’ time we might look back and pinpoint the ’20s as the decade it changed for this formerly overlooked and somewhat unloved grape.