WINE

The question “What do Crémant, Mousseux and Prosecco have in common?” would be a great one for trivia night in your local pub, writes Fiona McDonald. The answer can be gleaned from the story below.

fizzical

Let’s get

“Grandma’s socks” was the somewhat cheeky nickname for a very popular, slightly sweet sparkling wine which used to be made by Stellenbosch Farmers’ Winery before it merged with Distillers Corporation to form SA’s biggest liquor company, Distell.

The bubbly was Grand Mousseux and was reflective of a bygone era in South African wine when products usually had a French name to imply some kind of cachet. It’s why the vinho verde styled laughing-singing-dancing-eating-sharing white blend Graça was reminiscent of something Portuguese. Or white wines – generally blends – gave no indication of what was in them, simply labelled as Premier Grand Cru, Blanc de Blanc, Stein or even Cuvee Blanche.

"In France, there are eight appellations for sparkling wine which include the designation Crémant."

The world moved on and adopted more friendly varietal labelling so that consumers would know they were drinking chardonnay, sauvignon blanc, chenin blanc or even colombar – or blends thereof. Consumers have educated themselves with the help of wine producers – and this education continues as wine drinkers get to enjoy a broader range of styles.

Previously, sparkling wine was either Champagne – specifically from the geographical Champagne region of France – or not. South Africa officially adopted the term Methóde Cap Classique (MCC) in 1992 to distinguish its traditional method of making Champagne-style wines from other, simpler styles of bubbly. (And in an interesting aside, 2021 marks 50 years since the first South African version of the famous French fizzy wine was bottled locally in the form of Simonsig’s Kaapse Vonkel. And this wine also won its maker, Johan Malan, the bragging rights as Diners Club Winemaker of the Year for 2020.)

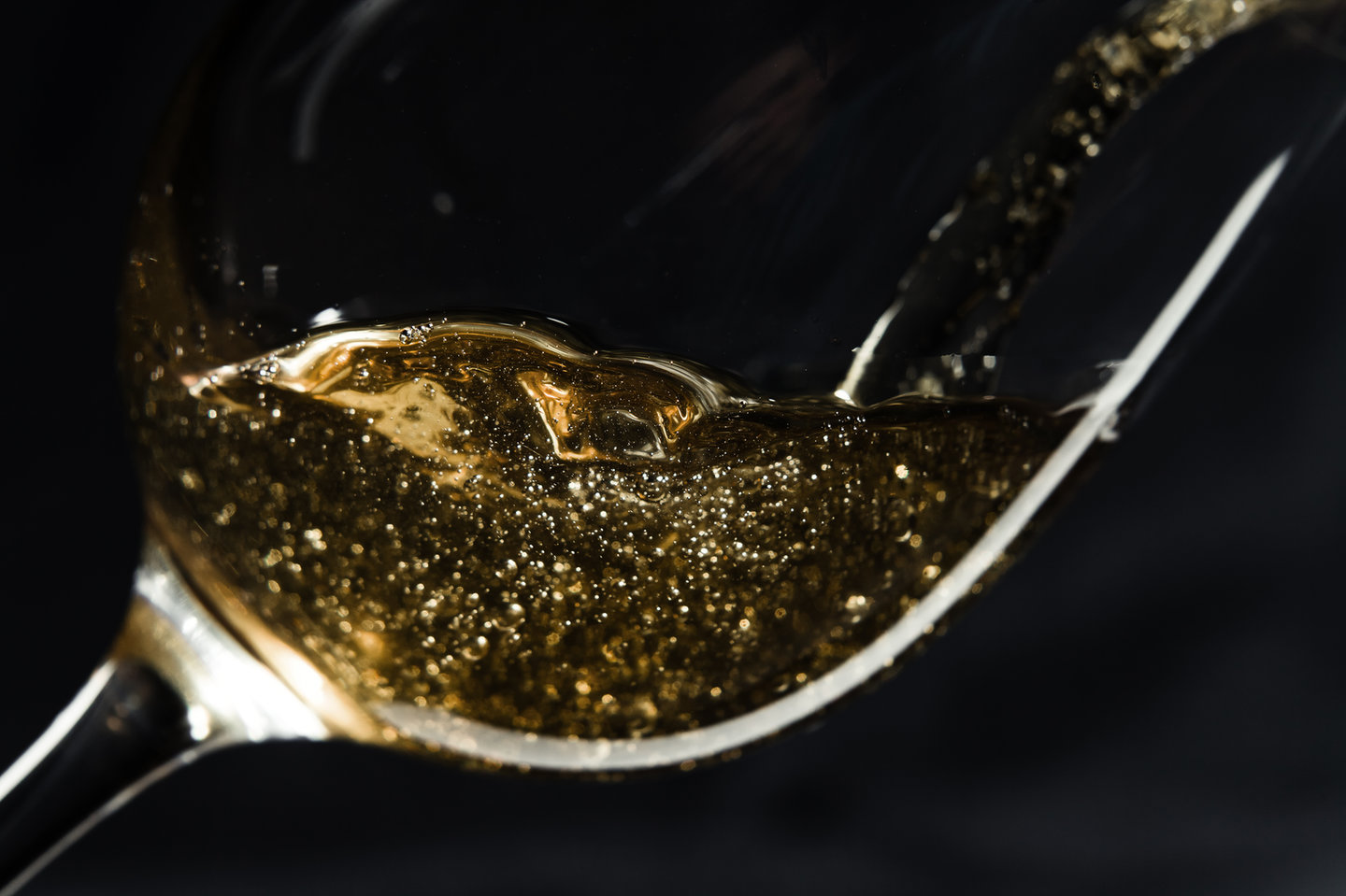

CHEERS magazine has covered the topic of Cap Classique before, the way that it undergoes a secondary fermentation in the bottle exactly the same as Champagne does. So what are the other kinds of bubbly out there? Short answer: there are many ... from Cremant to Cava to Prosecco and even more.

Sparkling wine gets its fizz, sparkle or bubble solely because of carbon dioxide – and there are different ways of making that happen. The most obvious one is to do what anyone could do with a Soda Stream – inject carbon dioxide (CO2) gas. The other “winey” method is by fermenting the wine again but not allowing the by-product of that fermentation – carbon dioxide gas – to escape. So by sealing it in a closed bottle, the CO2 remains within the wine until the bottle is opened.

Crémant, along with the term Mousseux, Wikipedia assures, are terms used for sparkling wine not made in the Champagne region. “Sparkling wines designated Crémant ("creamy") were originally named because their lower carbon dioxide pressures were thought to give them a creamy rather than fizzy mouth-feel,” Wikipedia states. “Though they may have full pressures today, they are still produced using the traditional method, and have to fulfil strict production criteria. In France, there are eight appellations for sparkling wine which include the designation Crémant in their name: Crémant de Alsace, Crémant de Bordeaux, Crémant de Bourgogne, Crémant de Die, Crémant de Jura, Crémant de Limoux, Crémant de Loire and Crémant de Savoie.”

Strict appellation production rules apply to the making of these bubbles, such as the tonnage of grapes per hectare as well as minimum ageing periods of one year – much the same as the requirements for South African Cap Classique which must also age in bottle for a minimum of 12 months.

But each one can differ, for example, in the permissible grapes. Crémant de Loire is the largest in terms of volume outside Champagne and is usually a blend of chardonnay, chenin blanc and cabernet franc grapes – whereas Crémant de Bourgogne must have at least a third of chardonnay, pinot noir and pinot gris while the rest of the wine is from the so-called inferior grape, aligoté.

"Prosecco also mixes well - hence its use in the popular summertime cocktail, the Aperol Spritz."

In the past two years Italian Prosecco has virtually exploded in popularity, particularly in the all important British market. An indication of its popularity is the number of bottles shipped to the UK in 2019 – 480 million!

Unlike Crémant or Cap Classique, this fizz is not made using the Champagne method. It’s done using the charmat technique, where the wine undergoes its second fermentation in a pressurised stainless steel tank rather than in individual bottles. Production time is 30 days so the bubbly is significantly cheaper to produce.

Prosecco is made in the north of Italy, in the region north of Venice, the Veneto and Fruili-Venezia-Giulia. The best area for Prosecco, given special denomination status, is in the cool, hilly area of Conegliano and Valdobbiadene. And the European Union decreed in 2009 that the Prosecco grape was renamed glera. It’s made in both a spumante – fully sparkling – or frizzante – lightly sparkling – style.

Until the 1960s Prosecco was quite similar to Asti Spumante, another Italian sparkling wine but from Piedmont, made from the fragrant and sweet moscato or muscat grape. Whereas Asti is low in alcohol at around 8% and known for its overtly grapey flavour, the style of Prosecco became ever drier over the years and now differentiates the level of sugar according to Brut, Extra Dry or Dry.

Although it is most commonly consumed like other bubblies, Prosecco also mixes well. Hence its use in the popular summertime cocktail, the Aperol Spritz. It’s also commonly used in the drink which made Harry’s Bar in Venice world famous – the Bellini, with fresh peach juice being the other ingredient. It makes a great mimosa with freshly squeezed orange juice too!

If Prosecco is notably commercial and customer and pocket friendly, there is something at the other end of the spectrum, a wine which is quite geeky or right up the bespectacled alley of wine nerds: pétillant naturel or methode ancestrale. (Pet-nat to those in the know ...)

“Pet-nat is almost like the year 2020 – you never quite know what’s going to happen!”

Local winemaker Corlea Fourie of Bosman Family vineyards is one of a handful of pet-nat producers in South Africa. “Pet-nat is almost like the year 2020 – you never quite know what’s going to happen!”

The way Fourie explained it, the winemaker is not in control of the process the way they would be when making Cap Classique or the traditional Champagne method. For MCC there is an initial fermentation to make a dry wine that is then re-inoculated with yeast for the secondary fermentation in bottle. With pet-nat it’s a one time shot, pressed grape juice is inoculated and immediately stoppered in a bubbly bottle until it’s ready.

As Eric Asimov wrote in the New York Times, it’s most likely how the original sparkling wine was made – even before the process of fermentation was understood and grasped by scientists such as Louis Pasteur.

“Millenniums before Pasteur, early winemakers, sensing that the fizzling, bubbling and ruckus of the fermentation process seemed to be complete, might have stowed their product in sealed containers. But if the fermentation had halted only temporarily, as sometimes happens in cold temperatures, it would begin again in the container when the temperature warmed.

“The creation of carbon dioxide in the confined space would either carbonate the liquid or, if the pressure was high and the container weak, cause it to explode.”

As Fourie explained the procedure, it’s a microcosm of making wine but in individual bottles – again with nowhere for the carbon dioxide to go other than be absorbed into the wine itself.

“Pet-nat is never ready during office hours ...” Fourie said. There’s no Monday to Friday, between 9 and 5 for this finicky wine child! “It’ll be the one that decides it’s ready to be bottled at 10pm on a Sunday night! It sommer does its own thing,” she said.

Her summation of this labour of love is that pet-nat is “the closest I can get to people or consumers experiencing what I as the winemaker do when I open a tap in the winery.” So it’s the vinified grape in its most natural, sparkling form.

“It’s for people who love wine – especially wine kept as natural as possible,” Fourie said, revealing that the most recent bottling of Bosman’s is a chenin blanc and there were only 2 200 bottles produced – most of which has been exported to New York where there’s a ready market for it.