Silent killer

Is there anything more annoying than the persistent whine of a mosquito dive bombing you while trying to sleep?! Yes, actually. A silent, deadly non-whining mozzie responsible for millions of deaths worldwide.

Malaria has been somewhat lost over the past two years of the global coronavirus pandemic. It’s a notifiable disease in South Africa with most cases being in a “malaria transmission belt” in low altitude areas in the north east – Mpumalanga, Limpopo and northern KwaZulu-Natal, bordering Mozambique and Zimbabwe.

Before anyone had heard of Wuhan or started paying attention to daily infection counts or what the symptoms of the many variants or mutations were, malaria was the world’s biggest killer. It accounted for almost 440 000 deaths every year, 90% of which occurred in Africa. All spread by mosquitoes during the annual rainy season.

The drastic Covid-19 death toll has removed this spotlight from malaria and has also impacted the initiatives which were slowly beginning to make inroads against the deadly parasitic disease.

“Every year that we let malaria spread, health and development suffers,” WHO regional director for Africa, Dr Matshidiso Moeti said in April 2021. “Malaria is responsible for an average annual reduction of 1.3% in Africa’s economic growth. Malaria-related absenteeism and productivity losses cost Nigeria, for example, an estimated US$ 1.1 billion every year. In 2003, malaria cost Uganda an estimated gross domestic product equivalent to US$ 11 million. In Kenya, approximately 170 million working days and 11% of primary school days are lost to malaria.”

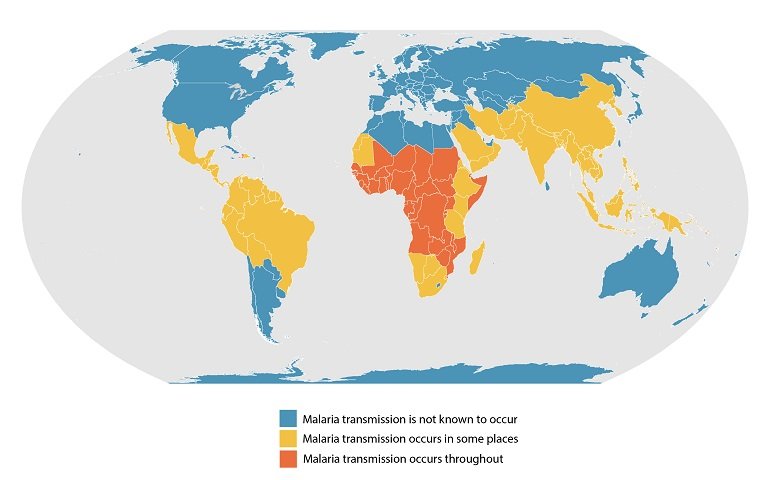

This map shows an approximation of the parts of the world where malaria transmission occurs.

Map source: Global Health, Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria

In 2020 the National Institute of Communicable Diseases wrote the following: “Increased malaria prevention and control measures are dramatically reducing the malaria burden. Globally, malaria is one of the six major causes of deaths from communicable diseases. 90% of the world’s approximately 440 000 annual malaria deaths occur in Africa. In the last few years, (2015-2019) South Africa has had between 10 000 and 30 000 notified cases of malaria per year, and the National Department of Health is planning to eliminate it (i.e. no local transmission) by 2023.”

And it wasn’t just about reducing malaria in South Africa – but in Namibia, Botswana and Eswatini too. The plan was to strive for zero deaths or transmissions by 2030 and efforts were proceeding well, in collaboration with the countries mentioned above, as well as Mozambique and Zimbabwe.

All indications were that significant progress was made. Statistics from the national Department of Health demonstrated that between 2000 and 2010 the malaria incidence rate was decreased from 11.1 cases per 1 000 head of population at risk, to 2.1 per 1 000. The battle was being won, with malaria nets, surveillance, vector control, insecticide spray programmes and community awareness.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) statistics make sobering reading: In 2019, almost half of the world’s malaria deaths happened in just six countries – Nigeria, Democratic Republic of Congo, Tanzania, Burkina Faso, Mozambique and Niger. And the most vulnerable age demographic were children under the age of five. They accounted for 67% of all deaths according to the WHO.

It’s not the anopheles mosquito itself that is the problem, but the plasmodium parasite which its bite deposits in the bloodstream. These parasites grow and multiply, first in the liver and then in the blood. And only when it’s in the blood do malarial symptoms develop.

There are three forms of malaria: the self-explanatory asymptomatic version when those affected have no signs of the disease other than the parasite circulating in their bloodstream; uncomplicated where the patient develops fever, chills, heavy sweats, nausea, headache, vomiting, diarrhoea and anaemia seven to 10 days after being bitten, and severe malaria which can lead to coma, organ failure, severe anaemia, lung problems and kidney injury or damage.

But there is hope. Because it has been an area of research for so long, with millions of dollars ploughed into studying the disease and its spread, a vaccine was developed. As Dr Moeti announced on World Malaria Day in April, the emerging results from a pilot scheme were “exciting”. “In 18 months, Ghana, Kenya and Malawi were able to deliver more than 1.7 million doses, reaching about the same levels of population coverage as other vaccines. This is a promising additional tool in malaria prevention.”

As South Africa (and Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Eswatini, Botswana and Namibia) enjoys the annual rainy season from September to April, the risk is high. Something acknowledged by Ross Holgate, son of adventurer Kingsley, who administers the Kingsley Holgate Foundation which has provided half-a-million insecticide treated mosquito nets to mainly mothers and pregnant women in the most affected regions in Africa.

In an interview with IOL Holgate said malaria prevention work in Mozambique had continued, despite Covid-19 lockdowns. “Our focus was on emergency provision of mosquito nets to mothers and children fleeing the northern Cabo Delgado province.” Heavy rains and flooding around the Limpopo river flood basin also exacerbated the situation.

Goodbye Malaria is a Foundation partner which undertakes spray programmes in the worst affected areas, regardless of international borders between SA, Mozambique and Eswatini. According to Holgate, more than 611 000 homes were treated in 2020, something he described as “a herculean task” during lockdown.

“If it wasn’t for the great work being done by Goodbye Malaria in stopping the spread of the disease from Mozambique into neighbouring countries, malaria would be even more rife in Eswatini, northern KwaZulu-Natal and in and around the Kruger National Park.”

Public health challenges abound. It’s important to remember that wars are never fought on only one front. As gains are made against Covid-19, the vigilance against malaria should not waiver.

BACK TO TOP