Discussing music, literature or art, people talk about “genre”. Since distilling could potentially be considered a creative art, that makes Irish whiskey one of the most exciting sub-genres currently thrilling spirit lovers.

Ireland’s

new chapter

Prior to 1990 it was possible to count the number of active distilleries in Ireland on the fingers of one hand – and you’d still have had a digit or two spare! (For the geeks, Cooley, Bushmill’s and Midleton were the three, although it must be noted that they were producing far more individual brands than just that trio.)

Post 2000 there has been the proverbial boom and the whiskybase.com blog currently lists 67! Teeling, for example, was the first new distillery in Dublin in 125 years and when it opened in 2015, it attracted 60 000 visitors in its first year. According to statistics published by the Irish Whiskey Association, global sales of Irish whiskey worldwide in 2020 accounted for 11.4 million cases – or a staggering 137 million bottles!

Yet another media release from 2021 once again clarifies the origin story of whiskey: “Irish whiskey is the oldest whiskey in the world and because we have been making whiskey for longer than any other nation, Irish whiskey has a depth and diversity unrivalled among other whiskeys.

“The first written reference to whiskey distillation came in the Red Book of Ossory, written in Ireland in 1324. This was nearly two centuries before the first written records of whisky distillation in Scotland.

“The Red Book of Ossory is believed to have been mainly written by Richard de Ledrede who served as Bishop of Ossory for 44 years from 1317 to about 1361. During this period, the Black Plague ravaged Kilkenny and it is believed that distillation formed part of the Bishop’s medicinal and pastoral response to the crisis.

“The Red Book of Ossory includes a recipe for Aqua Vitae which is the Latin term for ‘water of life’. In the Irish language this is known as Uisce Beatha or Fuisce which was anglicised as whiskey.”

There has been a concerted effort to promote Irish whiskey over the past year, the goal being for consumers to appreciate the depth and diversity within the category. The Irish Whiskey Association website is a treasure trove of information, podcasts and video clips.

The Red Book of Ossory on display in Kilkenny

Four distilleries which are leading the renaissance are Dingle, Roe & Co, Pearse Lyons and Slane.

“If there’s one thing you need in this game, its patience!” said sound engineer and now distiller Alex Conyngham who began Slane distillery in County Meath in 2009.

“Liquid to lips is so important in growing a brand,” he said which is why he made a point of attending as many whiskey trade shows and tastings as possible. “Getting people to taste your product as a smaller brand is invaluable.”

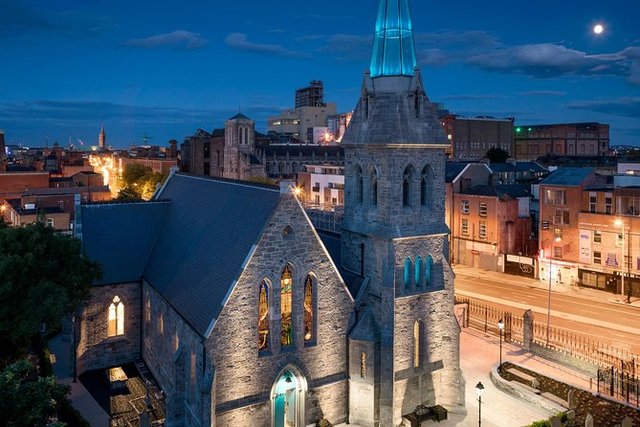

Conor Ryan of Dublin-based Pearse Lyons distillery which opened its doors in 2017 took a different tack with some of the first spirit off the stills sold as vodka and some infused with botanicals to make gin. He likened this strategy as having a Swiss army knife rather than a single bladed penknife! “You can engage a buyer about your rhubarb gin – and then tell them about something else in your product portfolio. I don’t think it detracts from the whiskey or the different gins. It makes good sense when dealing with larger markets.”

Visitors to the Pearse Lyons distillery can still be moved by the spirit since the whiskey is made in a renovated, deconsecrated church

Dingle did the same thing – and its gin is arguably more instantly recognisable and sellable than its whiskey currently. Master distiller Graham Coull said it was initially only intended for the local market but then it took off internationally! Nonetheless, he is confident that will change once the whiskey has aged in cask at the County Kerry warehouses. And that’s a major reason the two producers went the gin and vodka route: whiskey making doesn’t fit into the fast moving consumer goods category. It takes time to mature and age the spirit – and if you’re setting up a distillery, factor in even more years!

A prosaic warehouse is home to the Dingle distillery in County Kerry

Conyngham was also upfront about initially buying in spirit from Cooleys – although that ended in 2012. “I’ve always been very honest about sourcing spirit elsewhere when we were starting out,” he said. The Slane stamp was added by ageing it in their own casks for two years before release. By doing that he had a product for the market after just a year or two.

And setting Slane apart is the fact that it’s all about the raw material for Conyngham. “I grow barley,” he said, on 1 500 acres. “I’ve had a lot more fun turning it into whiskey rather than selling it off as animal feed. It’s also fantastic because of the role it’s played in the local economy, adding value through tourism.”

Respect for tradition and quality, as well as utilising home grown barley in its distillations, is just one of Slane’s selling points

The key is not to be different for difference’s sake, he said. The newbies were all carving out their own identity but doing so because they believe in having a point of difference. “But we’re lucky in Ireland because there is plenty of scope for innovation and difference – but also sticking to the rules and upholding quality. What binds us together is respect for the long tradition of Irish whiskey and Irish distilling.”

These distilleries are bringing old defunct buildings back to life – which is adding to the charm of the newbie category. Pearse Lyon renovated an old Dublin church, steeple and all, a project which took four years! Another shining example was the multi-million euro development of Roe & Co in an old power station in St James’ Gate, Dublin, formerly best known as the home of Guinness.

Diageo earmarked €25 million (R375 million) for the project to resurrect the brand, named for one of the largest distilleries in the golden era of Irish whiskey in the 1800s when it produced two million gallons of spirit annually. “The Roe & Co brand has been created to reflect modern, contemporary luxury in everything from the packaging to the whiskey itself. It will focus,” Diageo said, “on making Irish whiskey a more prominent part of Europe’s burgeoning cocktail culture, and will feature the finest hand-selected stocks of Irish malt and grain whiskies aged in bourbon casks.”

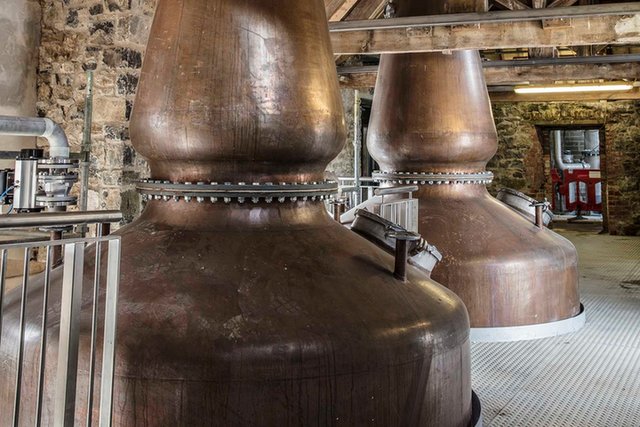

Roe & Co premises in Dublin, left. Note the extra bulb atop the neck of the middle still, a repurposed and rejuvenated Tanqueray gin still

Opened in 2019, both the master blender (Caroline Martin) and master distiller (Lora Hemy) at Roe & Co in Dublin are women – both of whom came to whiskey via perfume distillation and gaining experience in the Scottish industry.

Hemy shared some snippets in an online video, saying that the restoration of the premises had been a huge undertaking “but immensely fun”. “Our whiskey comes from a place of respect for tradition,” Hemy said, echoing Conyngham. “Innovation is something that’s been part of Irish whiskey tradition for 100 or more years.”

One such innovation was in rescuing a mothballed spirit still … a former Tanqueray gin still which had been tossed aside and was doing duty as a flowerpot before being renovated and put back to work by Roe & Co. (Incidentally, it’s an unusual form in that it has a second reflux bowl at the top, under the condenser arm joint.)

Ryan said the Pearse Lyons distillery stills came from Kentucky. It’s not a traditional pot still as the Irish know it so he had to work with revenue and customs to get it approved and written into the whiskey technical literature! “Change takes time,” Ryan said, “but at least it has set a precedent for other stills and producers coming behind us because the work’s been done.”

It takes time to put your own stamp on things but Ryan said it’s been a fantastic journey setting up Pearse Lyons. “The whiskey business is a long one and we’re new entrants. We’ve got whiskey that’s a 9-year-old spirit that’s not yet realised its potential. Whiskey needs to evolve - stills, materials, styles. We’re just venturing into our own grain – with 100 acres of barley and oats. We’ve different strains of yeast too. The taste difference is obvious but how does that equate five or 10 years down the line? It creates anticipation for what’s coming down the line.”

The age of internet has created an expectation of instant gratification, Ryan said. But whiskey can’t be rushed. They will just have to be patient, follow the journey of the distilleries over the years and anticipate what lies ahead.