Sensory

effect

When bloodhounds are on the scent, they’ll put their noses to the ground and follow the trail at speed, sometimes zigging left or zagging right to be back on track.

Humans have evolved – but do we really appreciate the amazing gifts we have? Sight, sound, touch and taste are all generally considered superior to smell. German philosopher and Enlightenment thinker Immanuel Kant considered it the most dispensable of the senses while Charles Darwin thought that smell was “of extremely slight service: to mankind”.

But in the early days of the pandemic, one of the first things to go was the sense of smell. So much so that it became a diagnostic tool before a PCR or lateral flow test confirmed Covid.

This phenomenon tickled the curiosity in many scientists who are now beginning to research olfaction – and anosmia – the official term for the lack of smell. Early Covid patients affected by it relate horror stories – of how food lost any flavour, about how everything smelled awful, rotten and utterly foul. For some, the sense of smell returned rapidly but for others it took months, along with a few other nasty long-Covid symptoms – breathing and extreme fatigue being just two.

There is still so much we don’t know about smell. Centuries ago smell or miasmas were considered harbingers of disease. Our modern efficient sewer systems are the result of engineers in the 18th century developing a method for whisking away foul-smelling waste water and learning how to treat this effluent and dispose of it.

One thing we do know, and that is dogs’ sense of smell is more refined than ours. The average canine nose has more than 300 million olfactory receptors compared to our 6 million. And the part of the dog’s brain devoted to analysing smells is about 40 times larger. This might count for nothing though, one scientist , a sensory neuroscientist at Rutgers University, John McGann wrote the following in The Smithsonian magazine:

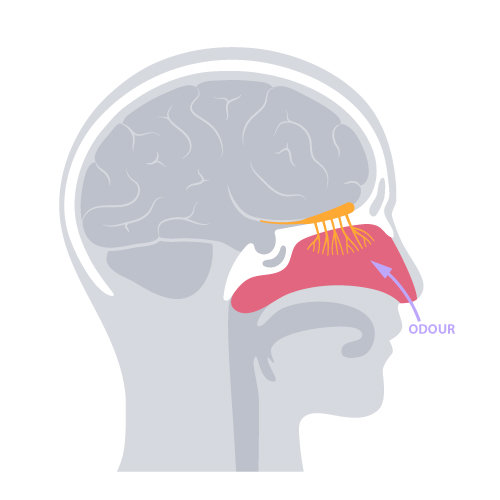

The science of smell – olfactory receptors transmit the odours from the nose to the olfactory bulb and ultimately to the brain which then interprets the smell

“The human olfactory bulb, which is five to six millimetres in width and only one third the volume of a dog's, may be plenty big enough to get the job done. After all, it's much larger than the same bulb in a mouse or rat, two animals that are considered to be strong smellers.”

Back to dogs: their sense of smell is more acute than scientific instruments. For example, they can pick up substances at concentrations of one part per trillion – which is like a single drop of liquid in 20 Olympic-size swimming pools! No wonder they are used as sniffer and detection dogs. Some researchers have also noted the canine ability to sniff out disease, picking up cancer before medical tests do. The use of dogs as companion animals for diabetes and epilepsy sufferers is becoming more common since they can sense the onset of symptoms before the patient is aware of a problem.

So how do we smell – and why is it that smells are so evocative? Whisky writer Dave Broom summed it up succinctly in his book on rum when he wrote: “Smells are gases which travel up the nose until they hit the olfactory epithelium and bulb situated bang between your eyes. From there, receptors carry the information to the brain, specifically to the limbic brain, which is the part that has the most to do with memory. That is why when you smell something, a picture snaps on in your head. Aromas are loaded with memories, often from childhood.”

Scotsman Dave Broom knows all about nosing whisky – and writing about their individual subtleties

Professor Barry Smith, an academic philosopher and founder of the University of London’s Centre for the Study of the Senses, said we think we only smell when we’re sniffing. “Not so, we’re constantly smelling because we breathe!”

It’s a sense that we only appreciate when we lose it,” he said in a TED talk. “When people lose their sense of smell it changes their emotional world.” Depression was a side effect of persistent anosmia. “And often depression lingers longer than it does in people who have lost their sight. There’s a huge reduction in the quality of life.”

Smell is emotionally loaded: think about your memories – of baking biscuits, the smell of the earth after a thunderstorm, suntan lotion on beach holidays …

“Because it’s always there we pay less attention to it,” Smith stated. However it has an important role to play in modulating moods, affecting attention and awareness as well as consolidating memory because it’s so strongly linked to the seat of emotions within the brain.

As wine tasters and parfumiers demonstrate, it’s the one sense that can be improved through training. You can’t improve your sense of hearing or eyesight through training but you can become more aware of how and what you smell.

And never forget that breathing deeply and smell can be therapeutic. There’s scientific evidence to suggest that the act of consciously appreciating the aroma of a flower contributes to psychological wellbeing.

BACK TO TOP